Architecture is a human act that invades and displaces the natural ecosystem. Biological order is destroyed every time we clear native plant growth and erect buildings and infrastructure. The goal of architecture is to create structures to house humans and their activities. Humans are parts of the earth’s ecosystem, even though we tend to forget that.

Logically, architecture has to have a theoretical basis that begins with the natural ecosystem. The act of building orders materials in very specific ways, and humans generate an artificial ordering out of materials they have extracted from nature and transformed to various degrees. Some of today’s most widely-used materials, such as plate glass and steel, require energy-intensive processes, and thus contain high embodied energy costs. Those cannot be the basis for any sustainable solution, despite all the industry hype.

Resource depletion and a looming ecological catastrophe are consequences of detachment from nature, and a blind faith in technology to solve the problems it creates.

Architectural theory, in the sense understood in this course, is a framework that studies architectural phenomena using scientific logic and methods of experimentation. Many experiments have been done by others, and we are going to apply them to architecture. Theory provides a model that explains investigations and observations about form and structure.

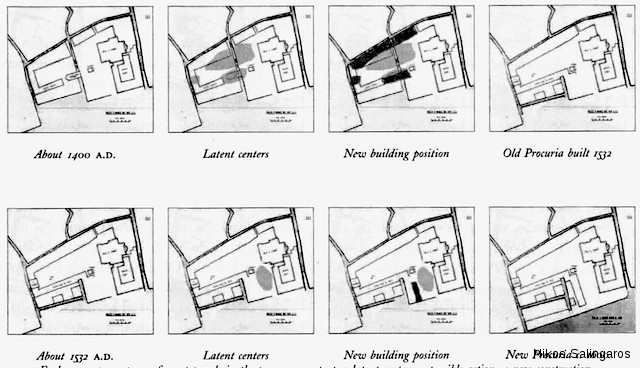

A successful theory will help us interpret what an architect does, even though each architect will likely have his/her own motivation and explanation. Nevertheless, the theory will allow us to compare among different types of buildings, and to evaluate how well those connect to users and with nature. We can understand how a building came about, and how it connects and interacts with its surroundings.

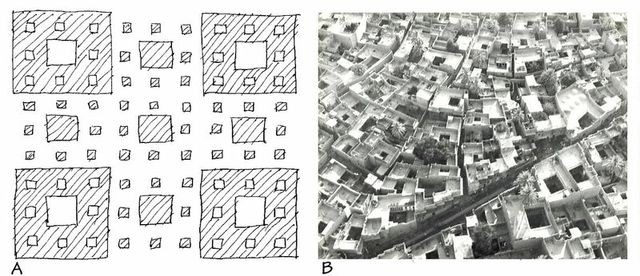

It will also be good if common people, not just architects, can understand architectural theory, and thus it should be formulated with that goal in mind. The advantages are that it is ordinary people who are going to inhabit those buildings, whereas architects can choose to live and work wherever they like. Another crucial point is that the majority of building activity is, and has always been, the erection of self-built informal settlements. People, not architects, build these structures.

Christopher Alexander has pioneered a theory of human-made order. It is based directly upon natural order, so there is neither contradiction nor confusion between the two types.

Alexander made five key assumptions that permitted him to pursue his work.

(1) Natural and artificial order rely upon the same mechanisms for their working.

(2) Natural order is self-organizing and self-correcting. What we observe is there because it works.

(3) Artificial order is not necessarily self-correcting, or maybe it is on a generational timescale so individuals are not going to notice it. As a result, human beings can do things to the natural environment and build buildings and structures that damage the world. It is not easy to diagnose what is good and distinguish it from what is bad.

(4) It is possible to use science to create diagnostic tools for what is good and bad in human creations—in how they affect the natural environment, including us humans.

(5) We can use the human body as a sensing instrument for what is good and bad in architecture. Basic assumption: human feeling is universal, and people share 90% of their responses, even if individuals come from different cultures or backgrounds.

To make good buildings, we need a worldview, a conception of the world that is healthy and that enables us to understand things deeply. A healthy worldview is based upon connectivity to the world: direct connection to the order of the universe and to natural processes as they are continuously occurring.

The opposite—detachment—leads to a dangerous condition where people analyze a situation as a mechanism isolated from the world. This is the model of a building or a city as a machine. Modern science is guilty of contributing to this disconnection from nature, since scientific models are necessarily self-contained and limited in scope—otherwise they would be useless.

Science gives us an excellent model of how something works as a mechanical system. Nevertheless, this is not a complete description even of the cases we do understand well. And there are a vast number of instances where we ignore any mechanical description at all of an observed phenomenon.

What is completely missing from a strictly mechanistic worldview is human consciousness, our personal and emotional connection to the universe. This might not matter when investigating some technical problems, but it’s all-important for things that affect us, like architecture. Another significant consequence is the lack of value in a mechanistic worldview. A human connected to the universe knows the distinction between good and bad, true and false, beautiful and ugly. These qualities are not relative, and are not matters of opinion. A consumer disconnected from natural values, by contrast, can be fed toxic products and be made to believe they are good.

The way out of the present, highly restricted view of the universe is to develop an immensely more connected state between humans and their environment. Attention is given to what affects us reciprocally with the world, when we are tightly connected.

Following this reasoning, people have a shared basis for judgment, and can intuitively judge whether something has order or life, and expect their gut reaction to be 90% shared across cultures and distances. In this new worldview, ornament plays a critical role to connect humans with the order of the world. Ornament is thus intimately related to function in the non-mechanistic sense.

We wish to consider architecture and the production of human artifacts also as essential components of natural ecosystems. Order and life are related. Natural things have an intrinsic order, and life as we usually know it and understand it is simply an extension of that order. For this reason, human constructions should not damage or contradict natural order.

The earth’s ecosystems (many of which are connected to each other) contain, and are contained by other components that neither metabolize, nor replicate. But every layer of the system is interdependent. This property of life in inanimate objects and situations arises out of their degree of natural order, and the human body has evolved mechanisms to sense that order. Thus, it is not surprising to feel that something is “alive”, because of its geometrical properties, even though that object is not biological.

Biological organisms have the additional features of metabolism and replication. A very simple consequence of thinking of a building as a “living” entity is that it requires repair and restoration. This analogy with metabolism takes us away from a central tenet of 20th Century industrial architecture: the quest for absolutely permanent and weather-resisting materials. This search has become very expensive. But worse of all, it denies living qualities. Materials that do weather in fact produce buildings that are more in keeping with biological organisms. For example, the Ise Shrine Complex in Japan is re-built every 20 years.

Buildings also engage in replication: if a form language is adopted by other builders, then the original prototype building is replicated in more copies, not exactly the same, but containing the same “genetic” information.

Since the perception of something as being “alive” is due to a very strong connection with our mind and body, there is a reciprocal effect: that object, place, or configuration makes usfeel more alive. It is possible to find myriads of artifacts, buildings, urban spaces that feel “alive” and that in turn make us feel “alive”. They invariably come from vernacular traditions and hardly ever from design.

The perceived living quality comes from specific geometrical configurations, and it is possible to discover the rules that generate a living quality. Even in non-traditional 20th-century examples of objects and places having perceived “life”, the life comes from their geometry. It is not based on concepts, or images, or fashions. By connecting to the thing, we feel that we are connecting directly with its maker, who therefore doesn’t hide behind any notions or ideas that contaminate its genuine character.

To get at a genuine understanding of architecture, it is useful to use the approach that scientists employ to discover nature’s secrets.

Edward Wilson outlines what science achieves:

(1) Systematic gathering of knowledge about the world, which is organized and condensed into basic principles as far as possible.

(2) Results must pass the test of independent and repeated verification.

(3) It helps to quantify information, for then, principles can use mathematical models.

(4) Condensation of information via systematization and classification helps in storage.

(5) A safeguard for truth comes from consilience: the horizontal links across diverse disciplines.

Consilience acts as a test for the soundness of a theory. Within itself, a theory might look good even when it contains fundamental flaws. Internal consistency can be misleading, since it could relate several false assumptions, but in a very convincing manner. We normally should be able to transition from one sound theory into another one that acts on a distinct domain. If there is a contradiction, then something is wrong. It could be that there is no barrier but a large gap, in which case that needs to be filled in.

Architectural theory can be formulated and verified by employing two mechanisms: internal hypotheses that are repeatedly verified, and external consilient links to other disciplines that have a verifiable basis. These include the hard sciences.

Good architecture is less of a reductionist discipline and must necessarily be a synthetic discipline. If it is applied in a reductionist manner, then it probably contains serious errors that damage the environment. To be adaptive means to synthesize many distinct responses to human needs and natural order.

Most important is for architecture to be directly linked to human evolution, the physical needs of the organism, and to use information according to evolved culture. Neglecting the biological origins of human needs and behavior detaches architecture from the world and from humanity. The architect should design a building that makes common people feel comfortable, and not to be liked just by architects. It should also adapt to its locality, not designed for somewhere else, or for no place in particular.